BIS Bulletins are written by staff members of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), and from time to time by other economists, and are published by the Bank.

The papers are on subjects of topical interest and are technical in character.

The views expressed in them are those of their authors and not necessarily the views of the BIS.

Why are central banks reporting losses? Does it matter?

Key takeaways

-

Rising interest rates are reducing profits or even leading to losses at some central banks, especially those that purchased domestic currency assets for macroeconomic and financial stability objectives.

-

Losses and negative equity do not directly affect the ability of central banks to operate effectively.

-

In normal times and in crises, central banks should be judged on whether they fulfil their mandates.

-

Central banks can underscore their continued ability to achieve policy objectives by clearly explaining the reasons for losses and highlighting the overall benefits of their policy measures.

Central banks have increasingly deployed their balance sheets in recent decades as a tool to pursue macroeconomic and financial stability objectives in support of their economies.

After the Great Financial Crisis (GFC), some advanced economy (AE) central banks used asset purchase programmes (APPs) or other lending programmes to achieve their policy aims.

Others introduced such programmes during the Covid- 19 pandemic (Graph 1.A).

These were funded mainly through interest-bearing commercial bank reserves, resulting in a declining share of interest-free liabilities (Graph 1.B).

In doing so and to pursue their policy objectives, central banks took financial positions, which influence their profits and losses as a by-product.

AE central bank balance sheets expanded since the FC and further with Covid-19

When central banks increase interest rates to curb inflation, their net interest income declines, since a large portion of their liabilities is linked to policy rates (Graphs 1.C and 1.D).

Asset valuations also decline with rising bond yields, putting further pressure on profitability for central banks using an accounting treatment that recognises changes in market values in calculating net profits.

Reflecting these dynamics, some central banks have recently reported losses, and more are expected to follow. In some cases and depending on accounting approaches, losses are sizeable and can result in negative equity.

This bulletin delves further into the drivers behind these developments and explores whether losses might complicate policymaking. While central bank profitability is also influenced by foreign exchange operations and valuations of international reserves (Box 1), the bulletin focuses on central banks with primarily domestic assets (generally AEs).

Why central bank finances are unique

Central banks are public institutions with policy mandates; they typically transfer their excess profits to the fiscal authority.

Whether losses matter for a central bank hinges on understanding the special nature of its finances, including that the usual concept of solvency does not apply.

A central bank’s balance sheet position, composition and inherent risk exposures affect its income. Its reported “accounting income” is calculated by applying the relevant accounting approaches.

From there, rules for profit distribution to the fiscal authority are implemented.

A typical central bank holds foreign and domestic currency securities on the asset side of its balance sheet, funded largely with banknotes in circulation and commercial bank reserves.

Traditionally, a central bank’s primary source of income is “seigniorage”, the net income earned on assets funded through currency issuance (a non-interest-bearing liability).

But income can also be driven by the impact of interest, market yield and exchange rate fluctuations on net interest income and asset valuations. To absorb losses, many central banks hold buffers as part of total equity (Archer and Moser-Boehm (2013)).

While central bank balance sheets are broadly similar, the composition of assets and liabilities varies in function of individual mandates and can change over time.

The increasing use of APPs by many AE central banks has raised government bonds as a share of assets. Correspondingly, the commercial bank reserves used to fund these APPs have come to dominate central banks’ liabilities.

Box 1 Exchange rate swings affect profits in emerging market and small open economies

While losses may be a new phenomenon for most AE central banks, many emerging market economy (EME) and some small open economy (SOE) central banks have experienced episodes of declining profits or losses (P&L).

After experiencing crises in the 1990s and early 2000s, many EME central banks accumulated FX reserves to self- insure against large swings in capital flows and exchange rates.

This drove balance sheet expansion, pushing up the average share of FX assets in total from 60% in 2000 to over 85% in 2019. While some EME central banks conducted domestic asset purchases and/or funding-for-lending programmes during Covid, FX reserves still account for most of their assets, making their profitability particularly sensitive to exchange rate swings.

For central banks with relatively large FX holdings, asset revaluation is the dominant driver of P&L. For many EME central banks, net interest income is typically small or even negative as the domestic interest rates paid on their interest-bearing liabilities (bank reserves or central bank bills) usually exceed earnings expressed in local currency on foreign assets.

Higher sovereign risk typically contributes to the negative interest rate differential or cost of carry. Income is also volatile. FX assets are reported in domestic currency at end-period exchange rates.

Large fluctuations of exchange rates vis-à-vis FX reserve currencies thus result in significant variations in reported income or losses (a domestic currency appreciation (depreciation) means the same FX assets will be worth less (more) in local currency terms). Historically, EME exchange rates have been volatile, making annual valuation changes typically much larger than the cost of carry and hence they are the main driver of profitability.

Approaches affecting reported accounting income and allocation

Rising interest rates and other factors can affect the timing, size and volatility of reported P&L (ie accounting income) and transfers to fiscal authorities in different ways at central banks with different financial frameworks.

The differences depend on three (potentially complementary) mechanisms: accounting approach, income recognition and distribution rules, and, in some cases, risk transfer agreements with the fiscal authority (Table 1).

These mechanisms help explain current differences across central banks in terms of when and to what extent they announce losses.

The three main accounting approaches (Part A in Table 1) affect the size and volatility of net income from asset valuations in the short term, although the results wash out over the longer term.

For central banks that use fair value accounting, eg the RBA and Bo, current losses from declines in asset valuation have been front-loaded, and future valuation gains will be reflected as revenue as the assets approach maturity. Others, eg the Eurosystem and Sveriges Riksbank, reflect declines in asset values in reported losses, but reflect unrealised gains only in revaluation accounts. For those that use historic cost accounting, eg the Federal Reserve, unrealised valuation changes are disclosed for transparency, but not recognised in reported income.

Income recognition and distribution rules

(Part B in Table 1) determine the size of buffers against losses. These vary considerably across central banks. Some can establish discretionary loss-absorbing buffers before accounting P&L is calculated (eg NBB and DNB). Some make the size of the profit distribution contingent on targets for various types of buffers (eg the Riksbank and Bo).

Some also use distribution-smoothing mechanisms, such as distributions based on rolling averages, to make profit transfers to government more predictable over a longer horizon. While these arrangements may reduce transfer volatility and offset accounting losses, they are unlikely to be sufficient to do so under all circumstances.

Indemnity arrangements

(Table 1, Part C may reflect a desire to insulate the central bank from the financial consequences of some policy measures. For example, the BE APF, established as a subsidiary to conduct APPs, is fully indemnified by the UK Treasury.

In other cases (eg RBNZ, the government authorised indemnities for specific operations without a subsidiary. In contrast, some central banks such as the RBA, do not have indemnities (Bullock (2022)).

Central banks that have indemnity arrangements view them as a way to ensure that policy measures are not constrained by the prospective financial impact on the central bank, thereby preserving independence. Some that do not have indemnities note that they are irrelevant from the perspective of the overall public sector balance sheet and could even risk reducing policy effectiveness if they weaken perceptions of central bank independence.

The consolidated impact of central bank profits

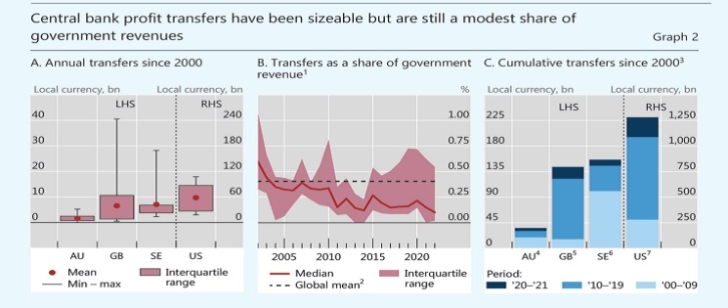

As central banks generally remit some or all of their profits to the fiscal authority, they are part of the “consolidated” public sector finance picture. Historically, and, especially in AEs, the central bank’s net income has been a modest source of government revenue (Graphs 2.A and 2.B). But when policy rates remained low in the post-GFC period (2010-19), central bank income and the corresponding transfers to government were relatively large compared with prior periods, contributing to government coffers (Graph 2.C. Recent losses for a number of central banks have led to smaller transfers to the fiscal authority or none at all, in some cases, probably for years to come.

Losses do not compromise a central bank’s ability to fulfil its mandate

While central bank losses will affect the consolidated public finances, serving as a source of revenue for governments is not the purpose of a central bank: they exist to fulfil their policy mandates, including price and financial stability. Thus, the success of their interventions should always be judged on whether they fulfil these mandates.

Unlike commercial banks, central banks do not seek profits, cannot be insolvent in the conventional sense as they can, in principle, issue more currency to meet domestic currency obligations, and face no regulatory capital minima precisely because of their unique purpose.

Accordingly, central banks are protected from court-ordered bankruptcy and are backed (indirectly) by taxpayers. These provisions allow central banks to successfully operate without capital and withstand extended periods of losses and negative equity.

History clearly illustrates this. Several central banks had negative equity yet fully met their objectives – for example, the central banks of Chile, Czechia, Israel and Mexico experienced years of negative capital. Between 2002 and 2021, some 10 out of 32 EME/SOE central banks had negative equity, only briefly in many cases, but for more than 30% of the time for three of them. But throughout, financial and price stability were maintained.

There can be, however, exceptional situations where misperceptions and political economy dynamics can interact with losses to compromise the central bank’s standing.

If there is macroeconomic mismanagement and the state lacks credibility, losses may erode the central bank’s standing, which may jeopardise its independence and could even lead to the currency’s collapse. The central bank’s credibility could also be at risk if it lacks sufficient resources to fund its operating needs, such as future earning capacity or government recapitalisation without conditional political influence.

Central banks are public institutions, but there is broad consensus on the need for their independence to pursue price and financial stability mandates without interference from governments, whose priorities can conflict with those mandates.

Achieving that independence has multiple dimensions, with a wide range of degrees and models across jurisdictions.

Financial independence – when a central bank has sufficient operational and financial resources to fulfil its mandate without influence – is one of these dimensions. Its attributes include determining its own operating budget and having clear protocols for the distribution of profits and dealing with losses. Crucially, episodes of negative equity or recapitalisation should not be an opportunity for the government to exert pressure on how the central bank discharges its mandates.

When there is uncertainty about how central bank losses will be dealt with, misperceptions can arise and erode central bank credibility. This underscores the importance of having a transparent financial framework so that stakeholders understand the unique nature of a central bank’s finances in the light of its mandates. The framework should include well-designed distribution rules governing transfers from the central bank to the government, processes for dealing with episodes of losses or reduced profitability, and clarity on risk-sharing arrangements if present. If these arrangements are codified and transparent prior to loss episodes, the risk that central bank independence could be compromised is significantly reduced.

Central banks’ response to losses: the role of communications

Central banks can mitigate the risk of misperception through effective communication to their stakeholders. They can clarify the context for potential losses, noting how the measures were undertaken to ensure price and economic stability over the medium and long-term for the benefit of households and businesses, which incidentally boosted economy-wide income and hence the overall tax base.

In their public communications, central banks can prepare stakeholders for losses at the outset of policy interventions, explaining that APPs or other programmes carry financial risk. And they can reiterate these messages when losses are imminent, explaining how central bank finances work and that losses are not relevant for policy.

Several central banks have already done so when publishing their recent financial statements or through other public communications. 11

To conclude, a central bank’s credibility depends on its ability to achieve its mandates. Losses do not jeopardise that ability and are sometimes the price to pay for achieving those aims (Nordstrom and Vredin (2022)). To maintain the public’s trust and to preserve central bank legitimacy now and in the long run, stakeholders should appreciate that central banks’ policy mandates come before profits.

The authors are grateful to Albert Pierres Tejada for excellent analysis and research assistance, and to Louisa Wagner for administrative support.

The editor of the BIS Bulletin series is Hyun Song Shin.

This publication is available on the BIS website (www.bis.org).

© Bank for International Settlements 2023. All rights reserved. Brief excerpts may be reproduced or translated provided the source is stated.